In an age defined by immediacy, the contrast between older forms of cultural engagement and today’s frictionless habits reveals more than nostalgia—it exposes a shift in how we relate to time, attention, and ourselves. Reading a paper book and playing an LP on a turntable share a set of deliberate gestures, sensorial demands, and small rituals that stand in stark opposition to the streamlined conveniences of modern digital life. These analog practices, once ordinary, now function almost as acts of resistance against a culture obsessed with speed and efficiency.

To read a paper book is to enter a tactile negotiation. The object requires physical interaction: the slight weight in the hands, the tactility of the paper, the soft resistance of a turning page. Each gesture anchors the reader in the moment. The book asks for slowness—an unbroken thread of attention that cannot be outsourced to an algorithm or accelerated by a playback-speed option. It is an embodied practice, It is the mind moving through sentences, the fingers marking a passage, the eyes tracing the typography. Reading in this way is not simply decoding words; it is a sensory choreography. The reader invests time and energy, and the book offers in return not just information but immersion, solitude, and depth.

Playing an LP on a turntable involves a similar choreography of intention. Unlike digital streaming, which collapses the effort between desire and gratification to a single tap, the LP demands commitment. One must select a record, slide it from its sleeve, place it carefully on the platter, clean the surface, set the speed, and lower the needle with precision. Even when the music begins, the listener is not entirely free; the album will run out, the side will end, and the record must be flipped. The entire experience honors the physicality of sound, the vulnerability of the medium, and the imperfection that gives analog audio its warmth. Listening to vinyl is not about convenience; it is about presence.

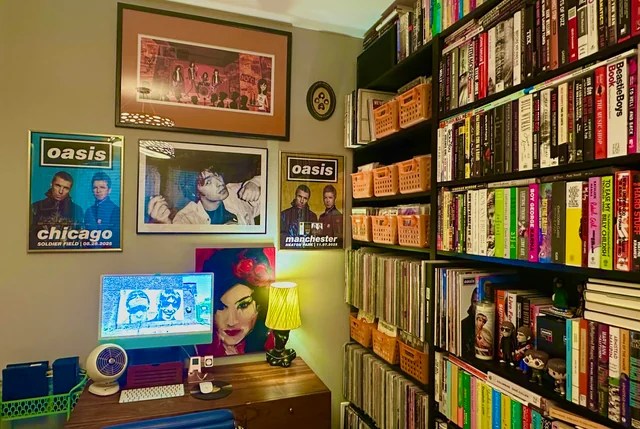

Physical media insist on occupying space, and that demand becomes part of their meaning. Books accumulate on shelves like sedimentary layers of a life lived among words; records stack in boxes or line walls, heavy with the weight of memory and intention. Unlike digital files, which vanish into the abstraction of a cloud, paper and vinyl anchor themselves in the geography of the home. They require care, maintenance, dusting, rearranging. They ask the owner to curate, to choose what deserves to remain. This spatial commitment is another form of complexity—one that marks not only the room but the reader or listener themselves, tracing a visible cartography of their curiosities and passions.

These older practices reveal that complexity is not a flaw—it is a form of meaning. The small inconveniences create conditions for attention. They oblige us to participate. They remind us that art is not merely consumed but inhabited.

Modern life, by contrast, is designed around the cult of ease. Digital reading collapses texts into endlessly scrollable surfaces, optimized for minimal friction. Streaming platforms ensure instant access to tens of millions of songs, each available with a tap, each interruptible, skippable, forgettable. Everything becomes quicker, lighter, and more accessible—but also more disposable. The logic of convenience reduces the weight of experience. If reading a paper book is a journey and playing an LP is a ritual, modern digital consumption often resembles passive drift: fast, shallow, and ephemerally satisfying.

The paradox is that our “easy” life often feels harder. We save time but seldom feel we have more of it. The constant availability of content fragments our attention; the seamlessness of technology accelerates our pace without enriching our experience. In removing obstacles, modern systems also remove anchors—those small frictions that once forced us into moments of presence, introspection, and sensory connection.

Thus, returning to a book or an LP is not regression but recalibration. It reintroduces intentionality to our daily rhythm. It places value on the process, not only the outcome. It restores complexity as a virtue: a way of slowing down, of granting one’s full awareness to a moment, an artwork, or a feeling.

In the end, the comparison is not between old and new technologies but between two philosophies of living. One treats experience as a craft that requires effort, stillness, and embodied attention. The other treats experience as a commodity to be consumed with maximum efficiency. To hold a book or to play a record is to choose presence over acceleration, depth over dopamine, and ritual over convenience. It is to remember that ease is not the same as fulfillment—and that sometimes, the difficulty is the gateway to meaning.

Dejar un comentario